Enfield revolver

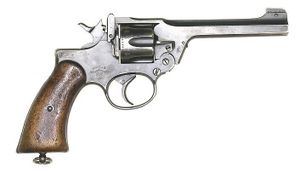

| Enfield Mk II Revolver | |

|---|---|

| Type | Service revolver |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1880–1955 |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | British colonial conflicts, World War I, World War II |

| Production history | |

| Designer | RSAF Enfield |

| Designed | 1879 |

| Manufacturer | RSAF Enfield |

| Produced | 1880–1889 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 11.5 in (292 mm) |

| Barrel length | 5.75 in (146 mm) |

|

|

|

| Cartridge | .476" Revolver Mk II |

| Calibre | .476 Enfield |

| Action | Double action revolver |

| Rate of fire | 18 rounds/minute |

| Muzzle velocity | 600 ft/s |

| Effective range | 25 yd (22 m) |

| Maximum range | 200 yd |

| Feed system | 6-round cylinder |

| Sights | fixed front post and rear notch |

Enfield Revolver is the name applied to two totally separate models of self-extracting British handgun designed and manufactured at the government-owned Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield; initially the .476 calibre (actually 11.6 mm)[1] Revolver Enfield Mk I/Mk II revolvers (from 1880–1889), and later the .38/200 calibre Enfield No. 2 Mk I (from 1923–1957).

The .476 calibre Enfield Mk I and Mk II revolvers were the official sidearm of both the British Army and the Northwest Mounted Police—as well as being issued to many other Colonial units throughout the British Empire—and the later model .38/200 Enfield No. 2 Mk I revolver was the standard British/Commonwealth sidearm in the Second World War, alongside the Webley Mk IV and Smith & Wesson Victory Model revolvers chambered in the same calibre. The term "Enfield Revolver" is not applied to Webley Mk VI revolvers built by RSAF Enfield between 1923 and 1926.

Contents |

Enfield Mk I & Mk II Revolvers

The first models of Enfield revolver—the Mark I and Mark II—were official British military sidearms from 1880 through 1887, and issue sidearms of the Northwest Mounted Police in Canada from 1883 until 1911.[2]

NWMP Commissioner Acheson G. Irvine ordered 200 Mark IIs in 1882,[3] priced at C$15.75 each,[4] which were shipped by London's Montgomery and Workman in November that year, arriving in December.[5] They replaced the Adams.[6] Irvine liked them so much, in one of his final acts as Commissioner, he ordered another 600, which were delivered in September 1885;[7] his replacement, Lawrence W. Herchmer, reported the force was entirely outfitted with Enfields (in all 1,079 were provided)[8] and was pleased with them, but concerned about the .476 round being too potent.[9] The first batch was stamped NWMP-CANADA (issue number between) after delivery; later purchases were not.[10] They were top-break single- or double-action,[11] and fitted with lanyard rings.[12] Worn spindle arms would fail to hold empty cases on ejection, and worn pivot pins could cause barrels to become loose, resulting in inaccuracy.[13] Its deep rifling would allow firing of slugs of between .449 and .476 in (11.4 and 12.1 mm) diameter.[14] Complaints began arising as early as 1887, influenced in part by the British switching to Webleys,[15] and by 1896, hinge wear and barrel loosening were a real issue.[16]

Beginning in late 1904,[17] the Mark II began to be in favor of the .45 calibre Colt New Service revolver, but the Enfield remained in service until 1911.[18]

The .476 Enfield cartridge the Enfield Mk I/Mk II were chambered for fired a 265 gr (17.2 g) lead bullet, loaded with 18 gr (1.2 g) of black powder.[19] The cartridge was, however, found to be somewhat underpowered during the Afghan War and other contemporary Colonial conflicts, lacking the stopping power believed necessary for military use at the time.

Unlike most other self-extracting revolvers (such as the Webley service revolvers or the Smith & Wesson No. 3 Revolver), the Enfield Mk I/Mk II was somewhat complicated to unload, having an Owen Jones selective extraction/ejection system which was supposed to allow the firer to eject spent cartridges, whilst retaining live rounds in the cylinder. The Enfield Mk I/Mk II had a hinged frame, and when the barrel was unlatched, the cylinder would move forward, operating the extraction system and allowing the spent cartridges to simply fall out. The idea was that the cylinder moved forward far enough to permit fired cases to be completely extracted (and ejected by gravity), but not far enough to permit live cartridges (i.e., those with projectiles still present, and thus longer in overall length) from being removed in the same manner.

The system was obsolete as soon as the Enfield Mk I was introduced, especially as it required reloading one round at a time via a gate in the side (much like the Colt Single Action Army or the Nagant M1895 revolvers). Combined with the somewhat cumbersome nature of the revolver, and a tendency for the action to foul or jam when extracting cartridges, the Enfield Mk I/Mk II revolvers were never popular and eventually replaced in 1889 by the .455 calibre Webley Mk I revolver.

Enfield No. 2 Mk I Revolver

| Enfield No 2 Mk I Revolver | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Type | Service pistol |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1932–1963 |

| Used by | United Kingdom & Colonies, British Commonwealth, |

| Wars | World War II, Korean War, British colonial conflicts, numerous others |

| Production history | |

| Designer | RSAF Enfield, Webley & Scott |

| Designed | 1928 |

| Manufacturer | RSAF Enfield |

| Produced | 1932–1957 |

| Number built | approx 270,000 |

| Variants | Enfield No 2 Mk I*, Enfield No 2 Mk I** |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 1.7 lb (765 g), unloaded |

| Length | 10.25 in (260 mm) |

|

|

|

| Cartridge | .380" Revolver Mk I or Mk IIz |

| Calibre | .38/200 (9.65 mm) |

| Action | Double Action revolver (Mk I* and Mk I** Double Action Only) |

| Rate of fire | 20–30 rounds/minute |

| Muzzle velocity | 620 ft/s (189 m/s) |

| Effective range | 15 yards (13 m) |

| Maximum range | 200 yd |

| Feed system | 6-round cylinder |

| Sights | fixed front post and rear notch |

After the First World War, it was decided by the British Government that a smaller and lighter .38 calibre (9.65 mm) sidearm firing a long, heavy 200 grain (13 g) soft lead bullet would be preferable to the large Webley service revolvers using the .455 calibre (11.6 mm) round.[20][21] While the .455 had proven to be an effective weapon for stopping enemy soldiers, the recoil of the .455 cartridge complicated marksmanship training.[22] The authorities began a search for a double-action revolver with less weight and recoil that could be quickly mastered by a minimally-trained[23] soldier, with a good probability of hitting an enemy with the first shot at extremely close ranges.[24] By using such a long, heavy, round-nose lead bullet in a .38 calibre cartridge, it was found that the bullet, being minimally stabilised for its weight and calibre, tended to 'keyhole' or tumble longitudinally when striking an object, theoretically increasing wounding and stopping ability of human targets at short ranges.[25][26] At the time, the .38 calibre Smith & Wesson cartridge with 200-grain (13 g) lead bullet, known as the .38/200, was also a popular cartridge in civilian and police use (in the USA, the .38/200 or 380/200 was known as the .38 Super Police load).[27]

Consequently, the British firm of Webley & Scott tendered their Webley Mk IV revolver in .38/200 calibre.[28] Rather than adopting it, the British authorities took the design to the Government-run Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield, and the Enfield factory came up with a revolver that was very similar to the Webley Mk IV .38, but internally slightly different. The Enfield-designed pistol was quickly accepted under the designation Revolver, No 2 Mk I, and was adopted in 1931,[29] followed in 1938 by the Mk I* (spurless hammer, double action only),[30] and finally the Mk I** (simplified for wartime production) in 1942.[31]

Webley sued the British Government for £2,250, being "costs involved in the research and design" of the revolver. Their action was contested by Enfield, who stated that the Enfield No 2 Mk I was actually designed by Captain Boys (the Assistant Superintendent of Design, famous for the Boys Rifle) with assistance from Webley & Scott, and not the other way around—accordingly, their claim was denied. By way of compensation, however, the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors awarded Webley & Scott £1,250.[32]

Variants

There were two main variants of the Enfield No 2 Mk I revolver. The first was the Mk I*, which had a spurless hammer and was double action only, meaning that the hammer could not be thumb-cocked by the shooter for each shot. Additionally, in keeping with the revolver's purpose as a close-range weapon, the handgrips, now made of plastic, were redesigned to improve grip when used in rapid double-action fire; the new handgrip design was given the designation Mk II.[33] The majority of Enfields produced were either Mk I* or modified to that standard.[34] The second variant was the Mk I**, which was a 1942 variant of the Mk I* simplified in order to increase production, but was discontinued shortly thereafter as a result of safety concerns over some of the introduced modifications.

The vast majority of Enfield No 2 Mk I revolvers were modified to Mk I* during WWII, generally as they came in for repair or general maintenance;[35] the official explanation of the change to the Mk I* version was that the Tank Corps had complained the spur on the hammer was catching on protrusions inside tanks, but most historians nowadays believe that the real reason was that the Mk I* version was cheaper and faster to manufacture.[36] When used in the manner in which British forces trained (rapid double-action fire at very close ranges), the No 2 Mk I* is at least as accurate as any other service pistol of its time, because of the relatively light double action trigger pull. It is not, however, the best choice for deliberately-aimed, long-distance shooting — the double action pull will throw the most competent shooter's aim off enough to noticeably affect accuracy at ranges of more than 15 yards (14 m) or so.[37] Some unit Armourers are known to have retrofitted the Enfield No 2 Mk I* back to the Mk I variant, but this was never an official policy and appears to have been done on an individual basis. Despite officially being declared obsolete at the end of WWII, the Enfield (and Webley revolvers) were not completely phased out in favour of the Browning Hi-Power until April 1969.[38]

The Enfield No 2 is very fast to reload—as are all British top-break revolvers—because of its automatic ejector, which simultaneously removes all six cases from the cylinder.

British combat experience during WWII with the .38/200 Enfield revolvers during WWII seemed to confirm that, for the average soldier, the Enfield No. 2 Mk I could be used far more effectively than the bulkier and heavier .455 calibre Webley revolvers that had been issued during WWI.[39] Perhaps because of the relatively long double-action trigger pull compared to other pistols capable of single-action fire[34], the double-action-only Mk I* revolvers were not popular with troops[34], many of whom took the first available opportunity to exchange them in favour of Smith & Wesson, Colt, or Webley revolvers.[40]

Ammunition

The Enfield No.2 Mk I was designed for use with the .38 S&W cartridge, now officially termed the 380/200, Revolver Mk I, but also known as the .38/200. It had a 200 gr (13 g). unjacketed round-nose, lead bullet of .359" diameter that developed a muzzle velocity of 620 - 650 ft/s (200 m/s).

Just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, British authorities became concerned that the soft unjacketed lead bullet used in the 380/200 might be considered as violating the laws of land warfare governing deforming or 'explosive bullets'. A new .38 loading was introduced for use in combat utilizing a 178-grain (11.5 g), gilding-metal jacketed lead bullet; new foresights were issued to compensate for the new cartridge's ballistics and change to the point of aim.[33] The new cartridge was accepted into Commonwealth Service as "Cartridge, Pistol, .380 Mk IIz", firing a 178 - 180 grain (11.7 g) full metal jacket round-nose bullet. The 380/200 Mk I lead bullet cartridge was continued in service, originally restricted to training and marksmanship practice.[33] However, after the outbreak of war, supply exigencies forced British authorities to use both the 380/200 Mk I and the .380 Mk IIz loadings interchangeably in combat. U.S. ammunition manufacturers such as Winchester-Western supplied 380/200 Mk I cartridges to British forces throughout the war.[41]

Other manufacturers

The vast majority of Enfield No 2 revolvers were made by RSAF (Royal Small Arms Factory) Enfield, but wartime necessities meant that numbers were produced elsewhere. Albion Motors in Scotland made the Enfield No 2 Mk I* from 1941–1943, whereupon the contract for production was passed onto Coventry Gauge & Tool Co. By 1945, 24,000[42] Enfield No 2 Mk I* and Mk I** revolvers had been produced by Albion/CG&T. The Howard Auto Cultivator Company (HAC) in New South Wales, Australia tooled up and began manufacturing the Enfield No 2 Mk I* and I** revolvers in 1941, but the production run was very limited (estimated at around 350 or so revolvers in total), and the revolvers produced were criticised for being non-interchangeable, even with other HAC-produced revolvers. Very few HAC revolvers are known to exist, and it is thought by many collectors that most of the HAC revolvers may have been destroyed in the various Australian Gun Amnesties and "Buy-Backs".

Users

See also

- Colt .38/200 Revolver

- Smith & Wesson .38/200 S&W M&P Revolver

- Webley Mk IV revolver

- .38/200

Notes

- ↑ Barnes, p.175, ".476 Ely/.476 Enfield Mk-3".

- ↑ Maze, Robert J: "Howdah to High Power", p. 37. Excalibur Publications, 2002.

- ↑ Phillips, Roger F., & Klancher, Donald J. Arms & [sic] Accoutrements of the Mounted Police 1873-1973 (Bloomfield, ON: Museum Restoration Service, 1982), p. 21.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 207 note 2 to Chapter 3; Sessional Papers, Vol. XVIII, No. 1, 1885, p. 164, & Sessional Papers 5-7, 1885, p. 265.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 23.

- ↑ A small number of Adams revolvers remained in possession of RCMP officers until 1888. Phillips & Klancher, p. 207 note 7 to Chapter 3.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 21.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 22.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 22.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, pp. 21 & 23.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 21.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, photo p. 22.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 21.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 21.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 22.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 23.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 23.

- ↑ Phillips & Klancher, p. 23.

- ↑ Maze, Robert J: "Howdah to High Power" (Excalibur Publications, 2002), p. 32.

- ↑ Stamps, Mark, and Ian Skennerton, .380 Enfield Revolver No. 2, page 9.

- ↑ Smith, W.H.B, 1943 Basic Manual of Military Small Arms (facsimile), page 11.

- ↑ Shore, C. (Capt), With British Snipers to the Reich, Paladin Press (1988), pp. 200-201

- ↑ Weeks, John, World War II Small Arms, London: Orbis Publishing Ltd. (1979), p. 76: the standard pistol training ammunition allocation per soldier was only 12 rounds per year

- ↑ Shore, C. (Capt), With British Snipers to the Reich, Paladin Press (1988), p. 201

- ↑ Shore, C. (Capt), With British Snipers to the Reich, Paladin Press (1988), p. 202

- ↑ Barnes, Frank C., Cartridges of the World, 6th ed. DBI Books (1989), p. 239

- ↑ Barnes, Frank C., Cartridges of the World, 6th ed. DBI Books (1989), p. 239

- ↑ Maze, Robert J., Howdah to High Power, page 103.

- ↑ § A6862, LoC

- ↑ § B2289, LoC

- ↑ § B6712, LoC

- ↑ Stamps, Mark, and Ian Skennerton, .380 Enfield Revolver No. 2, page 12.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Dunlap, Roy, Ordnance Went Up Front, Samworth Press (1948), p. 141

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Weeks, John, World War II Small Arms, London: Orbis Publishing Ltd. (1979), p. 76

- ↑ § B2289, LoC

- ↑ Wilson, Royce, "A Tale of Two Collectables", Australian Shooter magazine, March 2006.

- ↑ Smith, W.H.B, 1943 Basic Manual of Military Small Arms (facsimile), page 11.

- ↑ Stamps, Mark, and Ian Skennerton, .380 Enfield Revolver No. 2, page 118

- ↑ Smith, W.H.B, 1943 Basic Manual of Military Small Arms (facsimile), page 11.

- ↑ Stamps, Mark, and Ian Skennerton, .380 Enfield Revolver No. 2, page 79

- ↑ Shore, C. (Capt.), With British Snipers to the Reich, Paladin Press (1989), p. 201

- ↑ Hogg, Ian V., and John Walter.Pistols of the World, 4th Ed.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Hogg, Ian (1989). Jane's Infantry Weapons 1989-90, 15th Edition. Jane's Information Group. p. 831. ISBN 0710608896.

References

- Barnes, Frank C., ed. by John T. Amber. Cartridges of the World, p.175, ".476 Ely/.476 Enfield Mk-3", and p.174, ".455 Revolver MK-1/.455 Colt". Northfield, IL: DBI Books, 1972. ISBN 0-695-80326-3.

- Hogg, Ian V., and John Walter.Pistols of the World, 4th Ed. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications, 2004. ISBN 0873494601.

- Maze, Robert J. Howdah to High Power. Tucson, Arizona: Excalibur Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-880677-17-2.

- Phillips, Roger F., & Klancher, Donald J. Arms & [sic] Accoutrements of the Mounted Police 1873-1973. Bloomfield, ON: Museum Restoration Service, 1982. ISBN 0-919316-84-0.

- Smith, W.H.B. 1943 Basic Manual of Military Small Arms (facsimile). Harrisburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books, 1979. ISBN 0-8117-1699-6.

- Stamps, Mark, and Ian Skennerton. .380 Enfield Revolver No 2. London: Greenhill Books, 1993. ISBN 1-85367-139-8.

- Wilson, Royce. "A Tale of Two Collectables". Australian Shooter magazine, March 2006.

External links

- The Corps of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers Museum of Technology: Pistol Revolver .476 inch Enfield Model 1882

- The Corps of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers Museum of Technology: Pistol Revolver .38 inch No 2 Mk I and again

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||